Sound familiar? Your alarm didn’t go off as planned, so you quickly dress, rush through the kitchen, and grab a handful of something hot before frantically sprinting out the door and towards your destination. Now stop it right there. Pause the transmission. Let’s zoom in on that breakfast and make some notes:

- It’s a crispy piece of toast.

- Defying logic—and laws of physics— the toast is just dangling adorably out of your mouth as you race down the road at high speeds.

- No jam? Strange. No butter? Even stranger.

- This entire scene looks familiar…

Exactly! It seems you’ve fallen into one of the oldest anime tropes in existence: “Toast of Tardiness”. But it’s not entirely your fault. This plot mechanism has been used ad nauseam for so long that no one—not even ardent otaku—can agree on when its origins began. One thing is for sure though: it must be stopped and Niigata is just the place to do it.

“Rice Ball Girl”

According to the Niigata Prefectural Government, “repeatedly viewing such scenes in anime may have created an image in Japanese people’s minds that breakfast means bread, thereby resulting in a shift away from eating rice for breakfast”—and they’re not entirely wrong. After World War II, U.S. influence literally turned Japan upside down, starting with the inclusion of bread and milk in school lunches. Since then, rice has been on the decline in favor of a quicker and less messy breakfast alternative. In order to facilitate a rice comeback, an impressive PR campaign has been launched in Niigata.

As of February 2022, Chikoku suru omusubi shōjo, or “Late Girl with Rice Ball”, ads featuring Japanese actors and singers (Manami Igashira, Makoto Ogawa, etc.) have reached over 200,000 views. Apart from the attractive—yet clumsy—actors munching on various rice balls, the real star of the show is the rice itself: Koshihikari.

This particular brand of rice is now synonymous with Niigata. It maintains the highest rating of “Special A”, based on the 2019 Japan Grain Testing Association findings. But, as is mostly the case with greatness, the story behind this renowned grain is modest and almost didn’t happen.

However, if a scientist of agriculture were to sit you down and try to patiently walk you through the life span of koshihikari (especially in Japanese), it may work as a kind of sleep-inducing sedative, even to the keenest of students. Thankfully, a speed-walk through koshi’s “greatest hits” should suffice. With that in mind, let the tour begin.

Our Lord and Rice Savior

Namikawa Shigesukei

The year was 1931. Rice from Hokuriku, a snowy region on the Sea of Japan coast, wasn’t doing so well. In fact, it was famous for being disgusting and called “bird-rice” (鳥またぎ米), as in, “so bad, not even birds will eat it off the ground”. Enter our first main character: Namikawa Shigesukei, an agricultural engineer at the Niigata Prefectural Agricultural Experiment Station in Nagaoka. Like any savior, Namikawa performed miracles during his lifetime—3 of them:

Miracle 1 – created Japan’s first rice cultivar, “Norin No. 1”, a lifesaving rice that sustained lives throughout the war. An Early growth, high yield rice that actually tasted good!

Miracle 2 – “Norin 1″brought rice cultivation back to the Echigo Plain (the largest plain on the Sea of Japan side of Honshu)

Miracle 3 – Due to the success of “Norin 1”, the attention of the nation turned towards Niigata

Sadly, for reasons unknown, the nation lost Namikawa’s green thumbs to suicide on October 14, 1937. But his miracle rice would play a key role in the future of koshihikari.

Rice Rice Babies

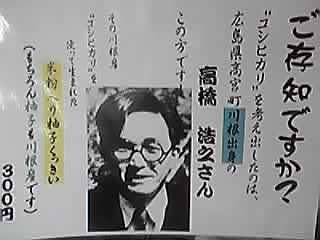

Takahashi Hiroyuki

Moving down the road, we wind up in 1940. As Japan was gearing up the war machine, a young breeding expert named Takahashi Hiroyuki became the head of the Nagaoka Agricultural Station. As the story goes, Takahashi and his team were playing a good old fashioned game of baseball, when Takahashi was kicked in the stomach and ruptured his pancreas, which fortuitously exempted him from the Imperial Draft. Safe from the war, Takahashi and a female colleague kept their heads down and worked hard on increasing food production and improving Namikawa’s “Norin 1”.

Around the same time, in Hyogo Prefecture, another cultivar, “Norin No. 22”, was just developed. It also had high yield, nice taste and—the most crucial— a high resistance to the most damaging of all fungal diseases to crops: blast disease (いもち病).

So, throughout the early 1940s, Takahashi used his exceptional skills to cross-breed father cultivar “Norin 1” with mother rice cultivar, “Norin 22”. The main issue with “Norin 1” was that it had low resistance to blast disease. Luckily, “Norin 22” had a high resistance, so it was the perfect artificial marriage. By 1945, the breeding was complete and—as we all know about the “birds and the bees”—babies would soon follow.

Takahashi was witnessing the early beginnings of koshihikari, but war complicated the situation. Most of the crops were destroyed, all except for the “Norin 1 + Norin 22” seedlings that Takahashi had lovingly planted. As any good father would do, he made sure that his little ones were safe and, in 1948, sent off 20 strains to the Fukui Agricultural Station for further testing.

The Foster Parent

Keiichirō Ishizumi

Whew! How is everyone so far? Still awake? You’re all doing so good. Moving on.

Takahashi’s rice babies were delicately handed off to Keiichirō Ishizumi, an agricultural doctor at the Fukui Station, who proved to be a worthy foster parent. Finally, after a lot of sweating and testing, Ishizumi struck gold with the successful strain, ”Echinan 17”. Like its forefathers, it had excellent quality and taste, but still fell short of the mark. For one, “Echinan No. 17” was pretty tall —1 meter or more—while other rice was 90 centimeters or less. Because of this, when the ear matured, it couldn’t bear its own weight and the stem would break and fall. Also, it still had a real problem with that pesky blast disease.

Men of “Light”

Masahiko Kunitake (left), Fumiyuki Sugitani,(right)

Thomas Edison, Walt Disney, J.K. Rowling and koshihikari: what’s the connection? Sometimes greatness isn’t obvious from the start. “Echinan 17” may have been flawed, but a few good men saw its potential at the newly established Niigata Agricultural Institute: Fumiyuki Sugitani, and his right hand man, Masahiko Kunitake. Sugitani was quoted to say, “the defects that can be improved by cultivation methods are not fatal defects”. In other words, “It works, so let’s not sweat the small stuff”. Their argument sold the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry and “Echinan 17” was eventually christened “Norin 100” in 1956.

As the men at the Niigata Institute were the first ones to embrace this new strain, they had the first crack at re-naming “Norin 100”. According to sources, it was Kunitake who was instrumental in the five-syllable katakana name. He found his inspiration in the golden color of the rice ears that resembled the sun: koshihikari; a combination of both koshi, referring to a historic 6th century province which included present-day Niigata, Fukui and Yamagata prefectures, and hikari, or light. In other words, “the shining light of Koshi”. And we got there in the end. Great job everyone!

Conclusion

The breakfast dilemma still remains: bread or rice. The “Late Girl with Rice Ball” campaign definitely makes onigiri sexier, but considering the long hard life these iridescent grains have had, the added historical context may be enough to sway toast-lovers over to the “light”. With this in mind, dear anime creators, the gauntlet has been laid down. Change is difficult, but it can also be delicious. It couldn’t hurt the plot to implement some fluffy, sticky and —most importantly—tasty koshikari rice into your character’s diet, or, at the very least, give them an alarm clock that works.

Check out the official site here: https://morning-omusubi.jp/

Experience the Youtube ads here: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC_8iGmzq007DHgv6PdcVWlQ

|

Even though Joshua Furr is from North Carolina (home of bluegrass, flight and Pepsi), he prefers a life outside the U.S. Currently you’ll find him in Warsaw, Poland.

He has a beautiful wife and two sons, all whom he forces to listen to Japan-based conversation and 80s music. Around lunch, he dreams about eating gyudon at Sukiya. When he’s not spending time with his family, he’s writing, teaching or tinkering with Adobe software. |